When the railway began to forge its way across the length and width of England, during the early parts of the 19th century, it was received with every emotion and expletive. But there was no way to stop it; in the name of progress the railway cut its way from up-and-coming industrial towns, such as Manchester and Birmingham, linking them and subsidiary towns to London. On its relentless journey it swallowed up farms, small villages, miles of countryside, and anything else that got in its way. Although, fortunately for us, to save the important history of our Capital, the railway companies were not allowed to demolish property across the West End and City of London, so the various train lines all culminated around the impoverished fringes.

It was in these fringes where, more often than not, the poor and working-class Londoners lived. Making way for the tracks and stations meant that often whole streets, if they had no importance, were ripped up and the needy residents spat out into other neighbouring and often overcrowded slums. As usual, the poor suffered as the rich got richer. Investors could make a fortune if they were brave enough and equally, for a hard-working man, there was at least the chance of regular employment

The train proved to have many benefits: deliveries of food and other essentials were faster and cheaper. This brought prices down – coal and flour for example. Journey time for travellers was reduced considerably, lowering costs and tedium, and a commuter workforce was able to travel by rail from outlying, sleepy-villages to better paid jobs in London. The building of homes around the still rural outskirts suddenly escalated; the villages became towns and, before long, were stretching out their impatient fingers towards the metropolis.

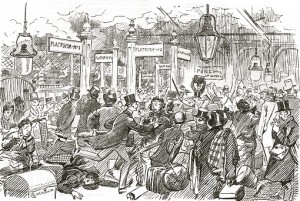

By the 1850’s the placement of the London train stations started to cause a problem. As the number of commuter’s grew, the London station exits began to heave with people needing to get across or around the West End and City to reach their daily destinations. The commuter’s were transported comfortably by the increasing number of horse-drawn vehicles, and the choice was good; an agile two-seater Hansom Cab for those in a hurry, a one horse Brougham for two, and a larger four-seater version called The Clarence with two horses and room for four passengers with luggage. This was commonly known as a “growler” due to the noise it made going over the cobbled streets.

For a cheaper ride there was the horse drawn Omnibus with an open air top deck and stairs at the back and, for group travel, a Charabanc, an early relation to the modern coach. Some travellers chose to go it alone on horseback but many had to walk. Adding to the melee were carts and wagons used for transporting goods.

By the late 1850’s the roads in the City and West End of London were badly congested; especially during the early morning hours and in the evening. It was the birth of the “rush hour”. Even the agile hansom cabs were having a problem – the roads had become dangerous, there were no traffic lights or rights of way, and pedestrians took their lives in their hands when they tried to cross the roads, dodging between the rolling wheels and horses hooves. Street lighting was poor and, during Autumn and Winter, London was prone to dense fog – “pea souper’s” – something would have to be done!

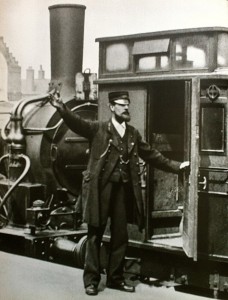

In January, 1863, the Metropolitan Underground Railway was opened, linking several of the London stations, and was the beginning of the “Tube” as we fondly call it now.