I sometimes sit outside the Blue Anchor pub, convivially situated by the River Thames, on the Lower Mall, in Hammersmith. Pint in hand, I watch the Thames ebb gently under Hammersmith Bridge on its way to the clamour of Central London. As I sink my pint, and consider getting another, I begin to wonder what it would have been like when the “Blew Anchor” was first licensed on June 9th 1722 and John Savery was the landlord.

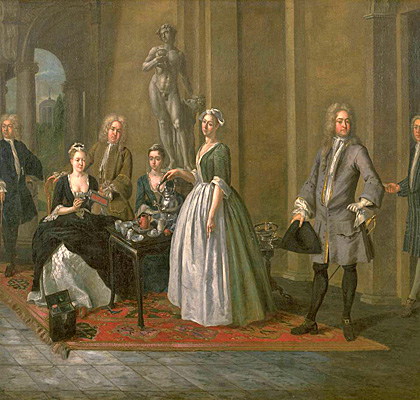

George 1 was on the throne – the monarchy was beginning to loose some of its absolute power and Robert Walpole was Prime Minister. Early Georgian Fashion was, for the wealthy, based on romantic fantasy, using beautifully embroidered silks. Long frock coats, wigs and large, ornately decorated hats were worn by men. Women wore tight, corseted bodices, full skirts with a draped mantua. Hair was worn close to their heads with a pretty lace cap. The poorer working classes would have been wearing a much plainer and probably second hand version.

The Blue Anchor is situated within the original boundary of the Hamlet of “Hamersmyth”, which spread out along the river, right and left from the main street, now known as Queen Caroline Street, and up to the Broadway. There would have been a village atmosphere with small houses and worker’s cottages with a range of shops providing essential goods.

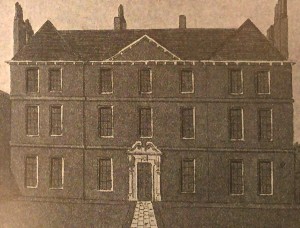

I try to imagine myself there, a resident of Hammersmith, sitting outside the Blue Anchor in 1722. John Savory’s wife has just brought me a tankard of ale. As I look to my right I see a few impressive, brick built, mansions, rounding the river’s bend towards the Chiswick Eyot; Rivercourt House, Hyde Lodge and Upper Mall House in particular. But none of these houses belongs to me and my family or I’d not be seated here enjoying my ale. I would more likely be employed in one of the mansions as a servant, like my doomed relative, Mary Goodfellow, working insane hours, scrubbing floors, polishing silver, washing clothes and emptying smelly night pots.

Or perhaps I’m a labourer, quenching my thirst after a long and thankless day toiling in the nearby market gardens. The fields stretch out like jewelled patchwork, as far as the eye can see. From behind the Blue Anchor up to Paddingwick Green, beyond the London to Windsor coaching route and around into Fulham. The once boggy and wooded land that surrounded Hammersmith has long been tamed and silt from the flooding river has, over the centuries, made the land around Hammersmith extremely fertile. There are a scattering of farmsteads, and adjacent rows of poorly-built worker’s cottages – one of which I’ll return home to later.

I can imagine oak trees and chimney pots, silhouetted against a pink evening sky. There’s a man with his son and two horse-drawn carts loaded with produce, setting out on their trek to the early morning markets of London City. I mustn’t leave the Blue Anchor too late – once it gets dark I’ll never be able to find my way home in the pitch black of a moonless night; and if a moon did light the way I might fall pray to thieves or perhaps be propositioned by a gentleman who thinks his money will buy him anything he wants.

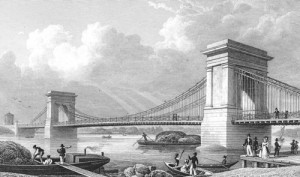

I look behind me and the bell tower of St Paul’s Church rises up in front of Butterwick House. To my left, the river’s span is interrupted by a flotilla of barges, with lightermen taking their tarpaulin covered cargoes to the wharfs to be unloaded. A waterman in his rowing boat comes into view, carrying two well-dressed gentlemen to a meeting down river. I suddenly realise that something is missing – there’s no bridge!

Hammersmith Bridge didn’t exist in 1722 and I am struck with a slight panic. I will have to rely on the Fulham ferry to get me and the Master’s coach and horses across the Thames when he wants to visit his family in Surrey. The Ferry leaves from the draw dock by the Swan Inn and arrives in Putney at a slope at the end of Brewhouse Lane. There have been reports that the crossing can be quite perilous in bad weather and the country roads from here to Fulham are full of stones and hidden ditches.

There is only one answer to this dilemma; we shall have to wait until 1729 when a wooden bridge will be in place at Fulham. The coach and horses can go by ferry and the Master and us servants can walk safely across the bridge.

As I sit quietly, draining my second pint and very much back in 2014, I become mesmerised by the sound of the River Thames as it laps up on the embankment. I remember my ancestors, and look over towards Castlenau, in Barnes. In 1824, Major Charles Boileau built Castelnau Villas, designed by the architect William Laxton. He then went on to build three rows of cottages called Castelnau Row, Castelnau Place and Gothic Cottages.

If I could really transport myself in time I would go back to 1841, when my 4 times great grandfather, Thomas Randell, and his wife, Hannah, lived just five minutes from the Blue Anchor, in Waterloo Street. I would join them for a jug of ale and a pie then we’d go for a stroll over the first Hammersmith Bridge.