Unlike the Victorians, when it came to holding a funeral, our earlier ancestors thought less about the pleasantries than getting their deceased relatives sent off quickly, cheaply and efficiently.

Britain had been besmirched with war, plague, cholera and, in general, a very short life expectancy. The 17th and 18th century funerals had few frills and flounces – just one or two pagan rituals such as the strewing of flowers and memorabilia over the grave; a practice which was soon banned. Not just because it was considered heathen but it interfered with the rights of ministers to graze their sheep or cattle in the graveyards. Instead of scattering flowers it became a practice to incorporate flowers and strong smelling herbs into the shroud, which helped improve the smell of the rotting corpse.

The Georgian funeral

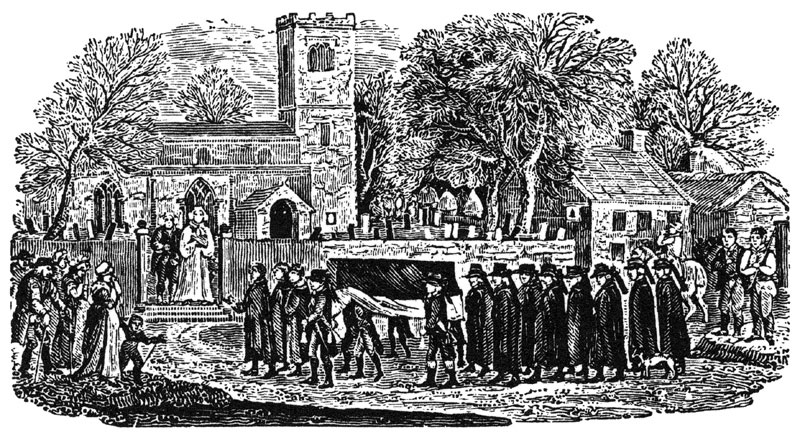

The arrangements were simple – the body was washed and wrapped in a shroud. The clergy would be informed and a grave digger employed. The male relatives, hats bound with long black ribbons, would walk in procession to the church, carrying the corpse on a bier covered with a pall. Females took part from a distance so that the ceremony was not ruined by their crying and fainting.

The pall and bier were usually hired: for a wealthy individual the more expensive pall would be used. This was made of black or purple velvet and was often elaborately embroidered. A very poor family might sometimes have been allowed to use the bier and a plain pall for free. The bodies, rich or poor, would simply be tipped or slid into the grave. The Bier and pall went on to be used again and again. Some churches owned a re-usable coffin, with a hinged bottom, from which the body was evacuated into the grave… very eco friendly!

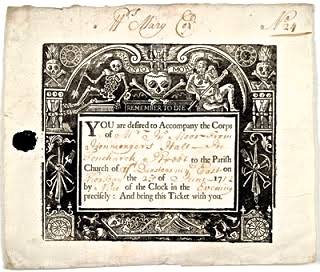

Invitation to a funeral 1712. The design shows a lack of regard for anything Christian, but I think it contains reference to the harsh reality of life and death as seen at that time.

Laws

The ceremony of sprinkling three handfuls of earth onto the body was introduced in 1542 as an official part of the funeral service and has continued, excuse the pun, religiously. A law, which has not always been taken too seriously through the ages, was made on the 30th December 1563. It stated that a body should be buried six feet under – a good and hygienic practice, particularly in times when contagious diseases had no cure.

But by the 18th century, and into early 19th centuary, the “six foot under” law was being flouted. Despite a high mortality rate, especially among children, the population had been increasing dramatically. The graveyards were filling up!

Children were not seen as a problem; their small corpses were usually placed into a grave of an adult that was being buried on the same day. The question which kept rearing its ugly head was, where to put all the potential extra corpses?

The first answer had been to build more churches with bigger graveyards. This worked in less densely populated areas but in cities, particularly London, by the time the Georgian period was in full swing, graveyards were seriously overcrowded. Some literally piled high – bodies on top of more bodies… packed side by side like sardines. Walls were built to retain the extra soil as the level of some graveyards began to reach the church windows. Bodies were being uncovered by dogs and eaten, and a constant smell of putrid flesh caused people to avoid going too close!

This seems to be no exaggeration. Tales of bodies rising from the grave might not have been far from the truth. If you look again at the first picture, “A Georgian Funeral”, the graveyard reaches the top of the walls and tombstones are clearly visible over the top.

During the reign of King William, in 1831, a cholera epidemic killed 52,000 people. The situation was now desperate and privately funded cemeteries began to spring up across England. It was a profitable business as the graves were costly to buy; the poor were still given a cheap and undignified burial, far away from their rich cousins.

The Victorians arrived, and decided that their relatives would be allowed to rest in style… at least the wealthier ones. With their growing fascination for death came superstition, new traditions, foolish and ghostly tales, and a desire to have a funeral to impress and make your neighbours jealous.

Superstition and traditions.

At the moment of a death, the curtains would be drawn: this let people know there’d been a death in the house. They would be kept shut until after the funeral. The eyes were closed and a coin placed on each lid. This was to stop the corpse staring back at you – the staring eyes were actually caused by rigor mortis.

Mirrors were covered: our reflection in a mirror is said to be the reflection of our soul – if the soul of the dead person should see itself it might not leave… or perhaps take another soul with it!

Dead family members were said to appear at the dying person’s bedside before death.

At the moment of death, pictures sometimes fall off walls. It’s unlucky if a clock stops at the time of death. Perhaps a raven might land on the roof, then there would certainly be a death. Some people said, if you see a white dove land on the roof of a house… a death would soon occur within. If you shiver suddenly… someone is walking over your grave – so beware.

The thing the Victorians feared most about death was not being dead. There were several things that might be carried out to prevent premature burial. One was to put a handbell in the coffin, another was to employ someone to stab you through the heart to ensure death. Wasn’t that what happened to Dracula? Another more popular way was to have a wake. This meant that relatives would stay awake and watch the corpse for several days and look for any movement. It also became a mark of respect.

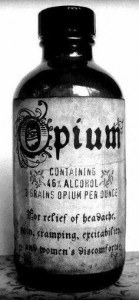

More than anything, the puritanical Victorians wanted a “good death”. They harboured images of a dying person surrounded by their family, sobbing into their perfumed handkerchiefs, telling each other what good and righteous lives they’d had and how much they’d loved each other. They also needed to repent their sins as, according to the church, there were only two places to go after death… Heaven or Hell. There would be no pain at death, it had been completely removed by such substances as arsenic, strychnine, mercury, opium, cocaine, morphine, quinine and chloroform – as long as you could afford it!

Instant mortality.

Locks of hair were taken from the corpse and woven into pictures or put into lockets. Photographs were taken of dead children, often propped up to look alive and, even more ghoulish… with their live brothers and sisters. Death masks were sometimes made to display in the house.

Mourning.

Mourning was an expensive business: black clothes, more than one outfit as formal mourning might last for up to a year. After black, purple or grey would maintain decorum. Mourning jewellery would be worn and black picture frames bought to show images of your departed loved-one. A man would need black ribbon for his hat and arm bands. This lack of male adornment is probably explained by the fact he was paying for it all.

Interesting facts

It is still quite legal to bury a corpse without a coffin, as long as you show no flesh near a public highway. It is also legal to bury your relative in your back garden or on common land as long as you have a certificate to prove that the corpse had no infectious disease such as the Black Death or Ebola.